In tenderheaded, Michaela angela Davis tells her life story with clarity, bravery, and care. As a journalist, stylist, and cultural force, Davis helped shape American media as we know it. In her memoir, VIBE’s founding fashion director speaks candidly about race, Black beauty, her career, motherhood, addiction, and survival in America.

tenderheaded opens with Davis’s agitation at the Rachel Dolezal scandal, which becomes a doorway into a deeper examination of colorism and whiteness in her life and in America. From there, the memoir moves into her childhood, tracing memories of grace, belonging, family instability, love for and from her grandmother, mental health struggles, and grief.

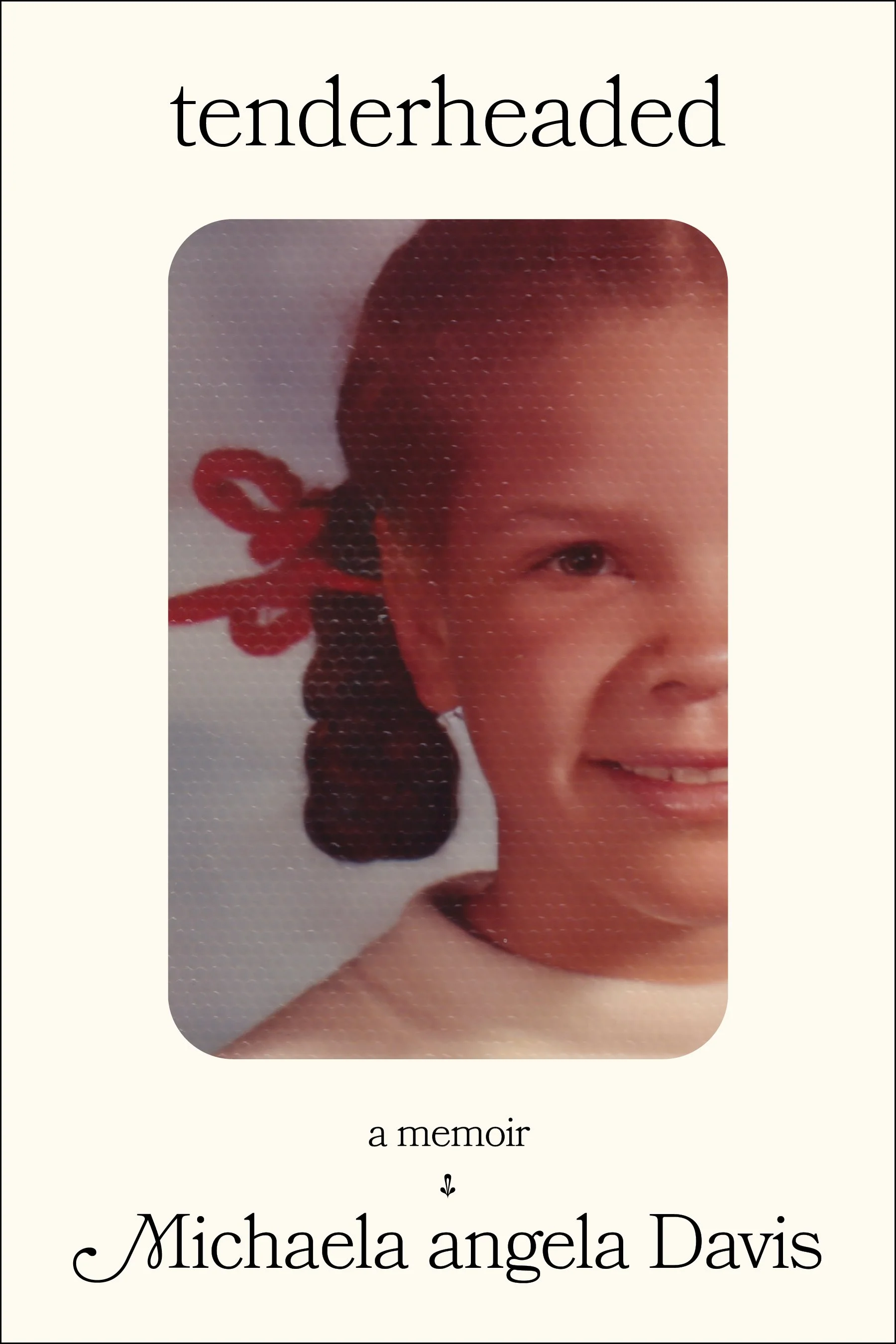

tenderheaded is filled with moments of beauty. Davis remembers discovering her sense of self through style, from her light hair to the pride she felt walking into a Black-owned hair salon and asking for an Afro. Tiny moments that are tender, grounding her later career in something deeply personal.

Davis also offers an inside look at her career, including her involvement in the rise of Black media and magazines in the mid to late 90s and early 2000s. She writes about brushing shoulders and witnessing the work of rising stars like Mimi Valdés, Shaniqwa Jarvis, and Hilton Als, and shares stories about styling icons like Prince, Diana Ross, Beyoncé, and Mary J. Blige.

She reflects on Essence and honors the magazine’s role in the “Black is Beautiful” era. She also acknowledges access and the reality for Black culture and fashion magazines. Even at the height of its influence, she explains, the fashion industry remained “by and large racist and misogynist.” The result was wasted talent and stalled dreams. “Just about every Black woman I ever knew had underutilized creativity,” she writes.

What gives tenderheaded its emotional weight is Davis’s honesty about her personal struggles. She writes openly about shame, financial fear, motherhood, and alcoholism. Her honesty about falling in love with drinking is striking. Admitting to readers that she struggled but never lost her sense of self-awareness: “When booze morphed me into a careless, annoying, talk too loud, touch too much, say the same thing over and over again weirdo.”

tenderheaded is written with care and confidence, as if Michaela angela Davis has been holding these words in for years. In telling her story, she offers more than a memoir. She gives us a clear look at what it means to live, work, and mother while Black in America, and insists that tenderness itself is a form of strength.

tenderheaded is moving, layered with history, and takes us through deeply personal moments in your life related to domestic abuse, mental health, addiction, identity, colorism, and survival. Why was it important for you to share so much of your life in the form of a book at this stage?

First, thank you. Human life, black women’s lives, are layered, made complicated by history, media and the narrow collective imagination. I believe if one is going to write a memoir, tell a story of their lives, ask people to spend money and time with their story, the author should, if they are capable, have the courage to tell the truth, a truth that could be in service of humanity. Make a connection that may result in inspiring someone and the ultimate goal is healing, wholeness, for myself, for Black women and all others.

You speak movingly about the loss of your brother Eddie and how his memory stays with you and continues to guide you. How has his spirit and your grief, in all of its forms, influenced your work over the years?

I became a specific kind of person because my brother was alive. I also became a specific kind of person because Eddie died. The profound grief and the spiritual expansion has influenced all aspects of my life. The impact has been more direct on my spiritual life.

When you write, “Instead of breaking a generational chain, I polished the links,” it feels like a profound acknowledgment of how pain and grief can move through generations. What does that line mean to you now, and how do you reflect back on it now that your daughter has her own children?

Yes, that’s exactly what that line reflects, how trauma can be inherited much like physical traits, and reframed in each generation. Yet, we can also heal generationally, I also believe we can heal our ancestors by doing the work of healing ourselves. I really believe that. My daughter is living proof of generational healing. She feels whole. Her daughter feels so clear, so free.

In your book, you reflect on working closely with icons like Prince, Diana Ross, Oprah, and Mariah Carey and holding powerful, glamorous editorial roles. Yet you mention that even at those heights, you often felt underpaid. Looking back, do you feel it was worth it?

It was “worth” it culturally, emotionally and historically. However, I, and many of my colleagues were underpaid, underrecognized and under protected.

From your perspective, has the fashion and magazine industry made meaningful progress when it comes to colorism, representation, and pay equity? Where do you still see the biggest gaps?

Well, I’m not even quite sure if there’s enough physical titles thriving to refer to it as a “magazine industry”. In the current political climate, I believe all industries are historically backsliding and suffering. The gaps are becoming gulfs again. Black women are being particularly targeted. It’s why I’m grateful tenderheaded is out now as an affirmation, a tribute to the power, beauty and vision of Black women.

We’re still living in a world where lighter skin often translates to privilege, even within our own communities. For readers who want to learn or unlearn these dynamics, what does it really look like to uplift and center Black women of all shades in media?

My hope is that tenderheaded helps expand and evolve our notions and conversations about “privilege” among Black women. What it means to us. It is no privilege to be separated from your sisters. I include the history of color caste system propaganda, policy and cultural practices in the US designed to keep us at odds, divided and distracted to give us some social and historical context. Black women have often been framed as being petty, jealous, neurotic when it comes to color and beauty standards. There have long been systems in place to create that frame.

You’ve worked with and mentored so many up-and-coming artists over the years. Who are some emerging designers, photographers, or creatives you’re most excited about right now?

I’m very excited about this generation of artists, creatives, many see themselves as multiplicitous. Sabla Stays, she designed my book. She does a lot of work with Saint Heron and Solange, whom I always watch. I love Solange’s new literary project. There’s a group of fashion designers in Bethann Hardison’s hub that are really exciting. I love A. Potts. I’m very excited about a young artist, a Duke Ellington School of the Arts alumni,

Yetunde Sapp. Again, I’m very excited for this generation.

As you look back on your life and work, how do you hope your story and tenderheaded will inspire the next generation of Black women navigating their own identities and creative paths?

My entire career, I would even argue my life, has been dedicated to being in service of, for inspiration of Black women and girls. I bet on Black women 3 decades ago. All my chips, I put all my chips on Black women. My hope is that tenderheaded serves as areference, a record of the beauty and complexity of our existence. I believe tenderheaded is my best writing. I believe Black women deserve my best. I believe Black women deserve the best from everyone.